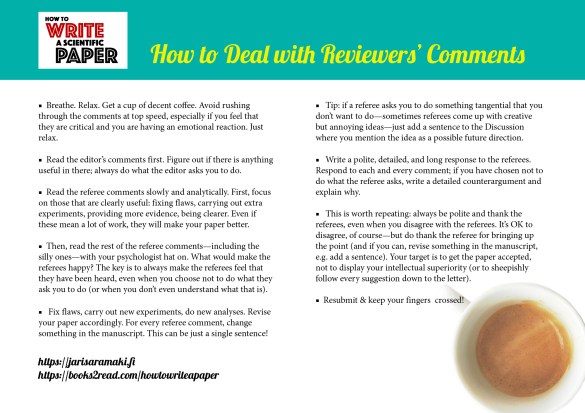

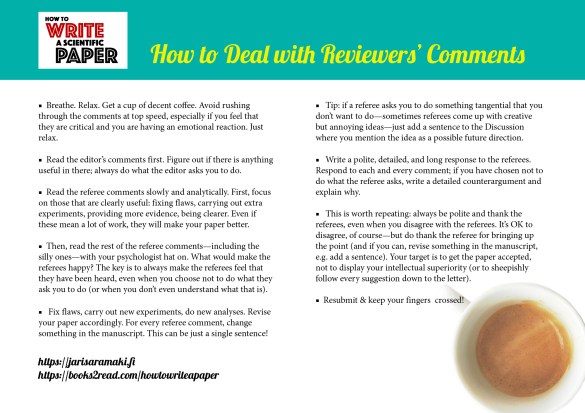

One more cheatsheet for scientific writing: this time the topic is reviewers’ comments—what to do when your receive the dreaded email from the editor with reviews of your manuscript?

For a hi-res PDF, click here!

One more cheatsheet for scientific writing: this time the topic is reviewers’ comments—what to do when your receive the dreaded email from the editor with reviews of your manuscript?

For a hi-res PDF, click here!

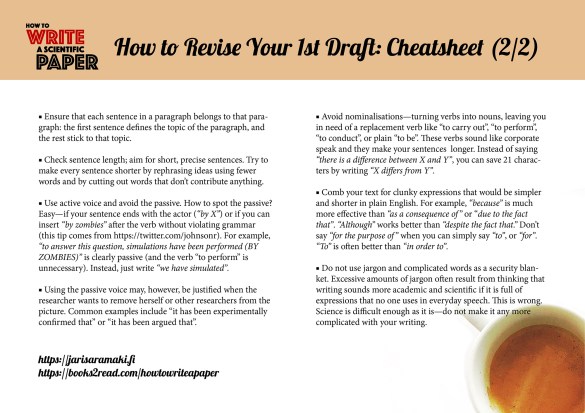

Here is the second cheatsheet on how to revise the first draft of your scientific paper, focusing on sentences and words. (Here is the first one if you missed it). Enjoy!

For a hi-res PDF, please click here!

Want more? In my book How to Write a Scientific Paper you’ll learn a systematic approach that makes it easier and faster to turn your hard-won results into great papers. Or check out the series of posts that starts here.

Hi all,

as I hinted at earlier, I’ll be releasing a couple of cheatsheets on scientific writing based on the writing series/book, mostly because I love to play with Adobe Illustra^H^H^H because I’m sure you’ll find them useful 🙂

Here’s the first one; click here for a high-res PDF version.

Want more? Get my little writing guide where you’ll learn a systematic approach to writing papers that makes the whole thing easier, faster, and less painful: How to Write a Scientific Paper!

This post continues directly from part 1/2.

One way of making the referees happy is to always acknowledge that they have been heard, whatever it is that they say. Never treat a referee with disrespect, even when what they propose is wrong, or when they have misunderstood things because they obviously didn’t bother to read your manuscript carefully enough. Always give them something.

If the referee misunderstood something that is obvious, write another sentence on whatever the obvious issue is and add it somewhere. Thank the referee for pointing out that your paper was not clear enough on the issue, and tell her that you have now added a clarifying sentence. If the referee’s comment or question is so confused that you cannot even figure out what it is that the referee wants from you, do something about it nevertheless. Pick some sentence or paragraph that might be related to whatever is confusing the referee. Then rewrite it: try to make it more clear, or at least rearrange the words… Finally, write a polite answer to the referee: tell that to the best of your understanding, her problem was probably related to the issue discussed in this sentence or paragraph, and that you have now tried to make it more clear. At times, the referee is confused enough not to know herself what the original issue was, and gladly accepts this act of repentance from you.

The above does not mean, however, that you should always do what the referee tells you to do. If the referee asks you to do something that you feel is wrong or doesn’t make sense, don’t do it. You should, however, explain in detail in your rebuttal letter why you chose not to do it. But, if possible at all, change something in the text, however small. Then, the referee will feel that she has been heard.

It is common for the referees to get speculative and to come up with so-called bright ideas. While this may be genuinely helpful, it can also be a nuisance if those ideas are tangential to whatever it is that you are doing. If the referee asks you to do something that sounds sensible but is clearly outside the scope of your paper, insert a sentence into your discussion section where you mention that it would be useful to do in the future whatever it was that was suggested by the referee.

It may also be that the referee is both hostile and wrong: you know that your results hold, but the referee does not believe you and does not want to believe you. In this case, you must make your stand and defend your results. Be polite, constructive, and firm. Why does the referee act this way? If it is because you have not provided enough evidence to support your conclusion, apologise for lack of evidence and provide more (even if there was enough already). If it is because the referee feels left out (often indicated by requests to cite some of her own work), you can give her credit for some earlier work in the introduction or discussion, but you should not cite papers only because you are forced to do so.

There may even be more nefarious reasons for referee hostility – the referee trying to block competition for instance – that may be hard to detect or disentangle from general grumpiness: perhaps the referee simply had too low blood glucose levels, you never know. Even if you suspect something like an attempt at blocking, be polite but firm while writing your responses in a way that they are also meant for the editor’s eyes. If someone has decided to block your work, you cannot turn that person’s head, but the editor might be able to spot what is happening. And if a referee is clearly being unethical, you should confidentially let the editor know this.

But most of the time your referees have good intentions: being critical is not the same as being mean. If you treat your referees with respect, if you make sure that they feel that they have been heard, and if you always give them something, they will be happy or at least happier, and because of this, they will accept your paper more willingly.

This concludes the series (for now). I may post summaries, cheat sheets etc later. Thanks for reading!

Breaking news: the ebook based on this series is out! Go get it!

Previously in the series: how to write the cover letter.

After several weeks or months of letting your paper out of your hands and into the cold and hostile world of scientific publishing, the dreaded moment of judgment finally arrives—if you haven’t been desk rejected by the editor in a few days, that is. There is a letter from the editor in your inbox, telling that you are either rejected outright or requested to revise your manuscript so that it can have a second chance. This statement is followed by detailed referee comments that may or may not make sense to you (or anyone else, for that matter). In theory, it is also possible to have the paper accepted as it is, but this is very rare: it has happened only once or twice during my career. Therefore it is safe to assume that there is more work to do now and that you have to get back to your paper. Often, this feels, at least to me, inexplicably painful, because the submitted paper has been neatly wrapped up and archived in my mind. I’ve gone on to think of other things, and now that perfect and beautiful wrapping has to be torn open – what a pain!

When receiving the letter, my suggestion would be to first take a few deep breaths and to try to calm yourself. This gets easier after dealing with tens of rejections and criticisms, but it never gets easy. Especially to PhD students who have put a lot of effort into their work and to whom this manuscript may represent 100% or 50% of their publication record, the moment of realising that someone is critical of their work is a difficult one.

What often happens at this stage is that you directly rush to the referee comments, and read through them at top speed. This is because you want to know RIGHT AWAY what it is that the referees find wrong with your beautiful work. And because you really speed through the comments, you only see the surface, and only pick up words that criticise your work. Your view is distorted.

Then, being a human, you get all emotional: angry, embarrassed, frustrated, depressed, or any linear combination of these. You may feel that your work is worthless, and therefore you are worthless. Please do not worry, feeling like this is as normal as it gets. You are certainly not worthless! We have all felt like this. This is what a career in science is about. Those who survive learn to persist and to deal with these emotions. It will get easier, and part of why it gets easier is that you learn that the process of peer-review can be very noisy and the referees can be wrong (they often are). And when they are not, you can use their criticism to learn and to improve your work.

When faced with a letter from the editor where referees UNJUSTLY criticise your work, my recommendation is to take a few more deep breaths, relax, calm down, and maybe do something else for a while. In particular, if the reviewers are very critical, your fight-or-flight-response prevents you from seeing what is really being said and what the really important problems are, and from assessing how difficult it would be to fix them for a revised version. So, get some distance first. Breathe, get a cup of coffee, look at a video of playing kittens or cute animals, and only then read the letter again, this time more slowly and analytically.

First, focus on what the editor says because this is the most important thing of all. As an example, I and my colleagues successfully got an article published where the referee hated the paper and asked for a total rewrite from a different and quite alien perspective. This rewrite would have been impossible for us to do. But the editor seemed to like the paper and told us that only a few minor things remain to be done. These two requests were completely at odds, but we chose to listen to the editor instead of the referee (nevertheless, we picked some of the referee’s points and cosmetically revised a few sentences, just in case). The paper was immediately accepted after resubmission.

So always listen to the editor! If the editor encourages you to submit a revised version, she is already on your side. Do it. If the editor uses less encouraging words like “should you wish to resubmit a revised version”, do it nevertheless, because even in this case the door is still open. Sometimes what you receive is a standard, copy-pasted response, and the editor takes no stance but leaves you to deal with the referees. In this case, just move on to the referees’ comments. But if there is anything in the editor’s words that you can use, use it.

Next, read through the referee comments carefully and with an analytical mind. First, look at the science and look at the positive side of things: did the referees spot any obvious flaws in your work? If so, great, now you can fix those flaws! Did they misunderstand your results? If so, great, this shows that you need to be more clear in your writing (even though referees often miss explanations that are already there in the manuscript…) Do the referees require some extra experiments or calculations to back up your conclusion? Do these make sense? If so, great, these experiments or calculations will make your paper more solid and you should do them, even if this takes time.

After you have gleaned useful and actionable information from the referee comments, look at what is left. There may be comments that you do not understand, comments that you understand but that you know are wrong, and all kinds of weird debris. The worst comments read like “I am sure that I have seen a similar result somewhere but cannot be bothered to find a reference”. Now, take off your scientist hat for a while, and put on your psychologist hat. You don’t have one? Get one, it’s tremendously useful. It pays off to realise that the referees are human. Humans are not analytical machines; humans have feelings. Your referees have feelings too. Figure out how they feel and what to do about it.

It is really worth the while to try to see the world through the eyes of the referees. Read the negative comments again, and try to understand what the referees think, feel, and expect from you. Do they feel irritated? Left out? Bored? Insecure, needing to bolster their confidence? Confused? Just plain cranky?

The key to getting your revised paper accepted is to understand what makes the referees happy, and then to give them this (while maintaining your scientific integrity, of course).

TO BE CONTINUED…

Previously in this series on how to write a scientific paper: ten tips for editing your sentences.

Now that you have revised and polished your draft and are the happy owner of a shiny new manuscript, one more step remains before you can submit it to a journal: writing the cover letter.

The cover letter is, in my view, mostly a historical remnant. Having to write one is, consequently, rather annoying. I can see that there may be some reason for cover letters for journals where the papers are too long to be skimmed by the editors, but even then, I doubt whether cover letters are of any use. Let me explain.

The point of the cover letter is to convince the editor that your manuscript is solid and important and that it fits their journal. But this is something that the abstract should do in the first place, especially if it follows the broad-narrow-broad formula outlined earlier in this series. The paper itself should do the job, too. In particular, the paper’s introduction should contain all the information that the editor needs to decide whether the paper is in the journal’s scope. It should also be enough for gauging whether the results sound believable and important enough for the paper to be sent to referees, instead of bluntly desk rejecting it. So why repeat all this information in a redundant letter?

So a big thank you to those journals who no longer ask for a cover letter.

Was I an editor, hard pressed on time, whose journal demands cover letters, I would highly appreciate a cover letter that is focused and short, say three to four paragraphs, max one page, preferably less. Here are two ways to write a short cover letter with only a few paragraphs and less than a page of text.

The better but slightly more adventurous way is to follow the inverted-pyramid schema that journalists commonly use for news stories. Most scientists are not used to writing this way! When following the inverted pyramid, you should begin with the most important thing and then proceed towards less important things, the nice-to-know details of the story, one by one and in order of decreasing importance. Tell what you have found in the very first sentence or two, then tell why your finding matters, and only then say something about how you obtained your results. Do not write a detailed explanation of your methods unless they are the key point of the paper; the editor is probably too busy to care, and if not, the details can be found in your manuscript. This way of structuring the letter is particularly suitable for those top-tier journals whose editors desk-reject most of the papers that they receive— they do not have the patience to search for the main point if it is buried somewhere on page two of your letter. They want to hear it first and then decide.

As a side note, the inverted-pyramid structure should always be used for press releases; those are read by journalists, not scientists, and journalists only get confused if they have to wade through lengthy introductory material before the main point arrives.

The other, more traditional way is to structure your cover letter in the same way as the abstract, or the Introduction section. Begin with the broad context, and then narrow the scope down and proceed towards your specific research question. After stating the question, tell what you have found out and how, and why what you have found out matters. But please be swift and move quickly: the first paragraph for context and question, second paragraph for the key result, and the third paragraph for significance.

You can also consider writing a hybrid version of the traditional cover letter and the inverted-pyramid lede. First, state your key result in a single-sentence paragraph: “In this manuscript, we show that X”. Then, follow the structure of the abstract and explain the context and the question in the second paragraph, a more detailed explanation of the result in the third paragraph, and an account of its significance in the fourth paragraph.

Whichever structure you choose, put emphasis on the implications and impact of your results. The why-does-it-matter part matters more than the how-did-you-do-it part, even if you have used particularly inventive methods. Do not exaggerate; rather, tell honestly what your work means. Whenever you feel like typing the word “very”, take a deep breath, command your fingers to stop, and jump directly to the next word.

Cover letter: if you have to write one, keep it simple, keep it short, put important stuff first, tell why your work matters.

Previously in this series on how to write a scientific paper: ten tips for revising your first draft

I have also condensed this post into a downloadable cheatsheet—click here for it!

After you have finished with your first pass and are now happy with the overall shape of things, it is time to polish the micro-level structure of words, sentences, and paragraphs. Once again, your overall goal should be simplicity, clarity, and readability. You can achieve this goal by cutting out everything that is not necessary. Condense and straighten your sentences so that they are short, to-the-point, and easy to follow. When editing your sentences, pay attention to these points:

Next: how to write the cover letter

Newsflash: the book based on this series is now available in most digital stores—click here for direct links!

Previously in this series on how to write a scientific paper: Zen and the art of revising and, if you didn’t read this yet, how (and why) to write a crappy first draft

“Don’t use big words. They mean so little.” -Oscar Wilde

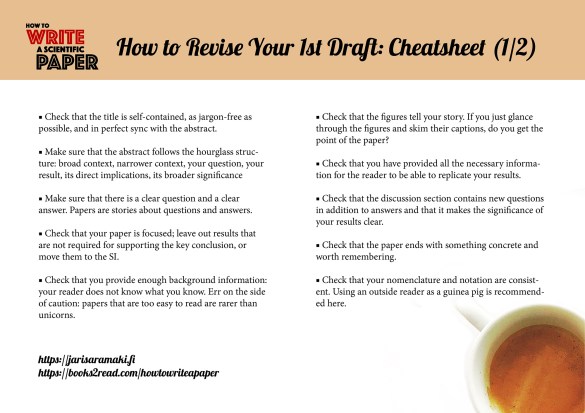

When editing and revising your paper’s first draft, my suggestion is to do two passes: first, a pass that focuses on the broader issues of structure and content, and then a second pass that focuses on the nitty-gritty, sentence-level details. In this post, I will present ten tips for revising your draft that can be used as a checklist for the first pass; this list contains issues that I frequently come across when working with students and revising papers.

If you have read this series this far, you won’t be surprised to see that most of the issues have to do with clarity and focus.

New to this series? It begins here: Why can writing a paper be such a pain?

[Previously in this series on how to write a scientific paper: how (and why) to write a crappy first draft

“If you feel the urge of ‘very’ coming on, just write the word ‘damn’ in the place of ‘very.’ The editor will strike out the word, ‘damn,’ and you will have a good sentence.”—William Allen White

If you have followed the advice in the last chapter, you should now be the proud owner of a crappy first draft of your scientific paper—a draft that serves as raw material, a draft that is for your eyes only, a draft that was written quickly and without too much care.

Now it is time for you to put on another hat and play a different role. It is time to look at your draft critically and to examine each and every sentence and paragraph ruthlessly so that you can cut out everything that doesn’t carry its own weight.

Before that, however, it might be a good idea to take some distance unless you are in a big hurry because a fresh pair of eyes can better spot what needs to be done.

How to revise your paper’s first draft? The process of editing and revising a scientific paper is iterative and it can take many rounds: my most-cited paper was at version number 27 or so when it was finally submitted. This may sound a bit excessive, but hey, it worked! You don’t always need to go to that length, though–just be sure to do several rounds of revisions, first alone and then with the help of your co-authors and/or your supervisor.

Just like with writing the draft, I recommend using a top-down approach when revising—begin with addressing broader issues before homing in on the details. First, read the draft quickly, without getting stuck on sentences, words, or other nitty-gritty details. Then, go through your findings: is the story logical, clear, and exciting? Does the abstract do its job and entice the reader? Is it clear what problem the paper solves? Is it clear what the solution is? Are concepts introduced in the right order? Is the paper balanced, or are there sections that are too long or sections lacking in detail?

Is it clear that your results are backed by solid evidence? Are the figures of a high quality and free of common errors such as microscopic label fonts? Does the paper begin with a proper lede – a sequence of sentences that frame the topic of the paper and entice the reader to read the rest of the story? Does the paper end on a high note?

The answers to the above questions may result in a need to “remix” the paper: to shuffle its contents around, to reorder things, and to completely rewrite some sections. This is normal: if you feel the need, just do it. Then, repeat the top-level analysis of your draft: answer the above questions again, and see if you can think of ways to improve the text further. If the answer is yes, do it. Repeat this loop until you are happy with the outcome and satisfied with the overall structure and flow of your paper. At this stage, you may even feel like returning to your research, say, to look for new results that back up your conclusion even more strongly. If so and if there is time, great, just do it, but please do remember to stop at some point because there will always be something new just around the corner. Leave some of that for the next paper.

When the overall structure is there, you should focus on the level of paragraphs and sentences. Use the same rules as for writing the paragraphs. For each paragraph, check that its topic is made clear in the first sentence or two. Check that the paragraph doesn’t stray away from the topic. If it does, cut it into two, or revise it. For each sentence, check that its meaning is clear, that it connects with the previous sentence, and that the rules outlined in the section on sentences below are fulfilled. Split sentences that are too long. Check the grammar. Use a spell checker.

Check your notation and nomenclature, and straighten them out if necessary. Do you always use the same word for describing a concept, or do you use several names for things? Is your notation consistent, do you always use the same symbols? Do you explain every symbol used in every equation?

Check your figures. Are your axis labels large enough to be seen without a magnifying class? (I repeat, this is the most common mistake in figures produced by PhD students, for reasons unknown to me: fonts whose size is measured in micrometers). Are your axis labels clear, and is the notation consistent with your body text? Are the colour schemes you use clear and informative, and most importantly, consistent across figures? Do the figure captions explain what should be learned from the figures, instead of only describing what is being plotted?

Then, finally, when all else seems in place, do a shortening edit, with the target of removing extra clutter and superfluous words. Make every sentence shorter that can be made shorter. Remove all adjectives, unless really necessary. Remove all repetition. Remove words that exaggerate things, because you sound more confident without them. Remove every instance of the word “very”, because you never need it. Remove the words “in order” from “in order to”.

When you are ready to show your improved draft to others, you can apply a technique that my research group has borrowed from the software industry: Extreme Editing.

In the software industry, extreme programming is one of the fashionable agile techniques, and part of this technique involves programming in pairs. So edit in pairs! Or, if there are more coauthors, involve as many of them as possible. Force your PhD supervisor to reserve several hours of uninterrupted quality time; you can argue that this co-editing session takes less time than several rounds of traditional red-pencil-comments.

This is how extreme editing works: go to a meeting room with a large enough screen and open the draft on the screen. Then, go through your text together, paragraph by paragraph and sentence by sentence. Be critical of each word and each sentence; look for sentences that are unclear and that can be misunderstood. Try to find ways of reducing clutter and shortening sentences. Cut out fat wherever needed. In my group, we jokingly keep a tally of points scored for every removed word. The winner is the one who has most ruthlessly killed the largest number of words that just tagged along, doing no real service to the text.

In the following two posts, I will present some more tips on how to revise your draft, first on the level of meaning and structure, and then on the level of sentences.

For the previous episode in the series on how to write a scientific paper, see here.

“To write is human, to edit is divine” -Stephen King

The best and most productive writers do not write perfect first drafts. The best and most productive writers write crappy first drafts and they do this as quickly as possible. They then edit, revise, and polish their crappy first drafts until those are no longer crappy (and no longer drafts). Or until the deadline makes them stop, whichever comes first.

This is what you should do with your scientific paper too: write the first draft quickly, and then edit, revise, polish, rinse, and repeat, until you are satisfied with the outcome. Or until the deadline comes.

If you have followed the system outlined in this blog, you are now at the point where you are ready to write your very own crappy first draft. You have a story, you have a structure, and you have notes for each section and each paragraph. If you have read the previous chapter, you have some idea of how to organize the building blocks of paragraphs and sentences (recap: the first sentences/words tell what the paragraph/sentence is about; stick to this and keep it simple; put weighty stuff at the end). This is all you need to know for now; I’ll provide plenty of tips for editing later.

So at the time being, put all rules aside, and aim to produce to a complete first draft quickly. Embrace the words of Stephen King quoted above and forget perfection when it comes to the first draft—let it be human, let it be imperfect. Let it be crappy! Why? Because producing and then polishing a crappy first draft is much, much faster than agonizing over every word and sentence and making only perfect choices that take forever to make. When all that time is spent on editing and revising instead, the outcome is much better.

Now that you have to finally produce some text, this is where the pain of writing typically hits you. Coming up with plans and storylines can be fun; writing rarely is. Writing is hard work. Writing the first draft is particularly hard work because not being self-conscious of your words is hard, and because not letting your inner critic stop you in mid-sentence is hard. These demons are difficult to wrestle but wrestled they must be, otherwise, there is no progress and the pages remain blank.

How to ease this pain, especially if you are a novice and it feels overwhelming? How to write all that text that needs to be written before you have a paper? There are some techniques that may help you.

First, make the first draft your own little (crappy) secret. It is not for your supervisor’s or co-authors’ eyes—it is for no-one else’s eyes, it is only for you, and it serves as raw material for editing only. When your supervisor asks you for the first draft, you should give her your second draft instead—by all means, call it the first draft! Keeping your first draft private should make you less self-conscious, at least in theory: no-one else will ever see it.

Second, aim at producing more text than you need. Just let the words come! At this stage it’s OK to have sentences that are too long, it’s OK to repeat yourself, it’s OK to explain the same thing over and over again with different words. In particular, if you are writing, say, one of those 4-page letters with a restricted word count, do not worry about the length at all. Just write. Cutting text is easier than producing it, and the editing phase easily reduces the length of your text by 10-30%. In my experience, the more, the better the final product.

Third, to be productive, schedule writing time and stick to it. Never wait for inspiration to strike, because it rarely strikes those who just sit there waiting. The Muses dislike idleness; they tend to show up when you are already engaged in work. Just sit down, put your phone on silent, remove all clutter from your screen, shut down your Internet access, and do it. Write. A good target is something like 30-45 minutes of uninterrupted writing, followed by a break. For a really good day’s work, four to five of such sessions are already enough. Just keep on doing this daily until you find yourself at the end of your first draft.

Fourth, if you get stuck, try changing the way you write. Take a pen and a notepad and walk away from the computer. Sit down somewhere, get a cup of decent coffee, and sketch your sentences on paper. Try to write as if you would be making lecture notes or just jotting down ideas. When unstuck, go back to your computer and use the material in your notes to continue. Or, instead of a notepad, try dictation, or go for a walk and play out imagined conversations in your head where you explain whatever it is that you are supposed to be writing to someone.

If you are very self-conscious and find it hard to make progress because of that nasty voice in the back of your head, you might want to try something along the lines of the Morning Pages technique. This technique provides desensitization by stream-of-consciousness writing: every morning you take a pen, a journal, and write longhand three whole pages, filling them with anything that comes to your mind. This may feel rather difficult at first; just keep on doing it. Morning Pages were introduced by Julia Cameron in her book The Artist’s Way as a tool for artists to connect with their creativity and overcome whatever fears hold them back. If you’d like to use this technique to help you write your paper, you can fill those three pages with thoughts on your research. See where this leads you.

If nothing else helps and it feels impossible to make progress, stop for a while and think about why this would be. What would need to change for the words to emerge from wherever it is that words come from? Usually, if I find myself in this situation, the answer is that the problem lies not with words or with writing but with thinking: there is something that I don’t yet understand, some pieces that don’t yet fit. Then, the solution is to stop writing (this part of the text, at least) and to solve the underlying problem instead. So take a time-out, and look for understanding first; the words will come more easily when you have found it.